Translate this page into:

Prevalence and characteristics of non-carious cervical lesions at the Ouagadougou Municipal Oral Health Center, Burkina Faso

*Corresponding author: Wendpoulomdé Aimé Désiré Kaboré, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Joseph KI-ZERBO University, Research Center of Health Sciences, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. dr_kabore@yahoo.fr

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kaboré WAD, Garé JVW, Ndiaye D, Kouakou KF, Da K, Faye B. Prevalence and characteristics of non-carious cervical lesions at the Ouagadougou Municipal Oral Health Center, Burkina Faso. J Restor Dent Endod 2021;1:46-52.

Abstract

Objectives:

This work sought to study the prevalence of non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) in a Burkinabe population consulting at the Municipal Oral Health Center of Ouagadougou.

Material and Methods:

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. It was carried out between August 1, 2020, and October 31, 2020. The study population consisted of all adult patients regardless of the reason for consultation. The diagnoses of abrasion, erosion, and abfraction were based on the morphology of the clinical forms of each of these lesions as already described in the literature.

Results:

During the study period, 595 patients were examined and 82 of them had at least one NCCL, for an overall prevalence of 13.8%. Abrasion lesions were the encountered the most (47.4%), followed by abfractions (27.1%) and erosions diagnosed in 25.5% of cases.

Conclusion:

NCCLs are pathologies of the neck of the tooth that is of great concern both in terms their clinical and etiological diagnosis as well as their therapy. The prevalence reported in this study is of importance to all oral health professionals, who need to be well aware that NCCL is increasingly a major reason for seeking care.

Keywords

Non-carious cervical lesions

Abrasion

Erosion

Abfraction

Prevalence

Burkina Faso

INTRODUCTION

Non-carious dental lesions are, by definition, wear and tear on dental surfaces that gradually lead to a loss of dental substance (enamel, dentin, and cementum) without bacterial action.[1] With such lesions, the phenomena leading to a loss of dental matter are independent of the carious process, which is microbial. They also differ, however, from alveolodental trauma, for which the loss of substance is abrupt, and the cause is usually a blunt force, whether direct or indirect.[2,3] This wear and tear can affect the occlusal part or it can occur in the cervical region of the dental crown. This last characteristic and the topographical location corresponds to a cumulative and progressive loss of mineralized tissue, localized at the enamel-cementum junction.[4-7] It is of particular interest due to the close relationship of the dental tissues that are present there, thus exerting an effect of duality in the management of the pathology but especially the multifactorial etiology to which it is subject. There are typically three distinct types of cervical lesion: Erosion, abrasion, and abfraction, and these are relatively difficult to distinguish clinically.[8,9]

The prevalence of non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) ranges from 5% to 85% depending on the various studies that have been carried out around the world.[10] In sub-Saharan Africa, it is in Senegal that Faye et al. already reported a prevalence of NCCL of 17.10% in 2005.[11] In Burkina Faso, only the work of Ndiaye et al.,[12] followed by those of Kaboré et al.,[13] all published in 2015, addressed the issue of NCCL. Unfortunately, these publications have still not made it possible to define an objective prevalence of NCCL because they targeted the professionals of oral health. In light of this lack of documentation, and to contribute to a better understanding of NCCLs, it seemed relevant to study these lesions by determining their prevalence within a Burkinabe population consulting at the Municipal Center for Oral Health (MCOH) in Ouagadougou.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Setting, timing, population, and type of study

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study that was carried out at the MCOH in Ouagadougou between August 1, 2020, and October 31, 2020. The study population consisted of all adult patients regardless of the reason for consultation.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Having consulted between August 1, 2020, and October 31, 2020;

At least 18 years old;

Provided informed consent to participate in the study.

The sample did not take into account:

Any patient with a health condition or disability that compromised their ability to directly answer the questionnaire used for the study;

NCCL of a temporary tooth, even if the tooth is persistent;

Patients lacking a tooth group (incisive-canine group, premolar group, and molar group).

The sample was selected using the non-probabilistic convenience method. Thus, all patients in the study population who met the eligibility criteria were selected.

Data collection

The data collection technique was a combination of maintenance and clinical observation. Our main data collection tool was a questionnaire comprising two subheadings that collected sociodemographic information (age, gender, occupation, and place of residence) and clinical data of the patients (reason for consultation, type of NCCL, side of the most affected tooth, and oral hygiene). Oral hygiene was determined using Greene and Vermillion’s Simplified Oral Hygiene Index.[14]

NCCL diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of each of the lesions was based on the morphology of the clinical forms of NCCL already described in the literature.[15,16] The first criterion was the geometric shape of the lesion; the second was the color of the tooth at the level of the lesion; and the third criterion was the surface condition of the lesion when assessed. The fourth criterion was the presence of lesions or associated manifestations such as wear of the occlusal surfaces, gum recession, dentin sensitivity, and the presence or not of tartar in the worn cervical area.

Abrasion was diagnosed in case of the following clinical picture:

Lesions on a group of teeth (several neighboring teeth);

“V” lesion with steep edges, elongated in the mesiodistal direction;

A smooth and hard base when assessed with a dental probe;

From up close, one can see marks reflecting wear from a toothbrush;

Absence of tartar in the impact zone and associated gum recessions are characteristics of cervical abrasions.

Abfraction lesions were diagnosed according to the following criteria:

Isolated or generalized lesions;

“V” lesions in the form of a slit that is clearly deeper than wide, with sharp edges and acute angles;

The lesion appears to be hard with a rough surface when assessed with a probe;

There are worn surfaces in occlusion. There can be associated tartar and malocclusions.

Erosion lesions were found through the following semiology:

A lesion that is wider than it is deep;

A U-shaped lesion with preservation of a residual cervical strip of enamel;

The bottom of the lesion is hard and appears polished without presenting a rough surface;

From an early stage of being etched, the lesion becomes yellowish and translucent (dentin color);

When it occurs, the lesion is associated with other erosive spots on other portions of the tooth besides the cervical region. Spontaneous or provoked hypersensitivity (probing and spraying) remains one of the key characteristics of erosive lesions.

Execution of the collection

The consultation team consisted of a dental surgeon and a nurse specialized in dentistry as well as two student trainees in the final year of dental surgery. These staff members participated in training regarding the use of the questionnaire and the diagnosis of NCCL. The clarification of the technical terms and their translation into the local languages of Mooré and Dioula was carried out for this purpose. A pre-test validated the tools and defined an average time per respondent before the official collection. The data collection was carried out in a consultation room equipped with a dental chair and scialytic lighting. The clinical observation was conducted using the following equipment: A dental examination tray (probes N°6, N°17, a periodontal probe, mirrors, tweezers), articulating paper, a cooling spray, a camera, and pens. Before the dental examination, the teeth were cleaned and dried using a cotton swab to remove plaque and residue. The clinical examination was conducted with great care to make the differential diagnosis concerning the clinical form, and the final diagnosis was confirmed by the dentist. The overall verification of the records was carried out before the data were entered.

Data processing

The information collected was entered into a form created using EPIDATA software. The data analysis was carried out with EPI-info 7.1.3.3 software. We conducted a detailed descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic and the clinical characteristics. The results are presented as frequencies and percentages.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample

During the study period, 986 adult patients were received for a consultation. Taking into account the eligibility criteria of the study, 391 patients were excluded, mainly due to oral emergencies involving limitation of the oral opening (cellulitis or bone fractures with trismus) and sizeable edentulous areas. We, therefore, ultimately retained 595 patients (60.3%).

Overall prevalence of NCCL

A total of 82 of the 595 patients who were examined in this study had at least one NCCL. The overall prevalence of NCCL was, therefore, 13.8%.

Sociodemographic data of the respondents

The 40–60 years of age bracket was represented the most (51.2%), with extremes of 20 and 79 years. The average age was 46.28 ± 12.92 years. There were more male patients (62.2%), and the sex ratio was 1.64. Civil servants were the most represented professional category (36.6%), and 6 (7.3%) patients resided in rural areas [Table 1].

| Variable | Number of patients, n=82 | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 20–40 | 25 | 30.5 |

| 40–60 | 42 | 51.2 |

| 60–80 | 15 | 18.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 51 | 62.2 |

| Female | 31 | 37.8 |

| Area of residence | ||

| Rural | 6 | 7.3 |

| Urban | 76 | 92.7 |

| Socio-professional status | ||

| Farmer | 4 | 4.9 |

| Pupil/student | 5 | 6.1 |

| Housewife | 9 | 11.0 |

| Official | 30 | 36.6 |

| Retired | 12 | 14.6 |

| Informal sector | 22 | 26.8 |

NCCL: Non-carious cervical lesion

Clinical data

During the consultation, 41 individuals (50%) mentioned tooth pain as the reason for their consultation. Patients with good oral hygiene with an Oral Hygiene Index (OHIS) between 0 and 1.2 accounted for 41.5% of the total number [Table 2].

| Variable | Number of patients, n=82 | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for consultation | ||

| Tooth pain | 41 | 50.0 |

| Prosthesis application | 17 | 20.7 |

| Dental sensitivity | 11 | 13.4 |

| Esthetic | 7 | 8.6 |

| Other* | 6 | 7.3 |

| Greene and Vermillion SOHI | ||

| 0; 1.2 | 34 | 41.5 |

| 1.3; 3 | 32 | 39.0 |

| 3.1; 6 | 10 | 12.2 |

| Not evaluable** | 6 | 7.3 |

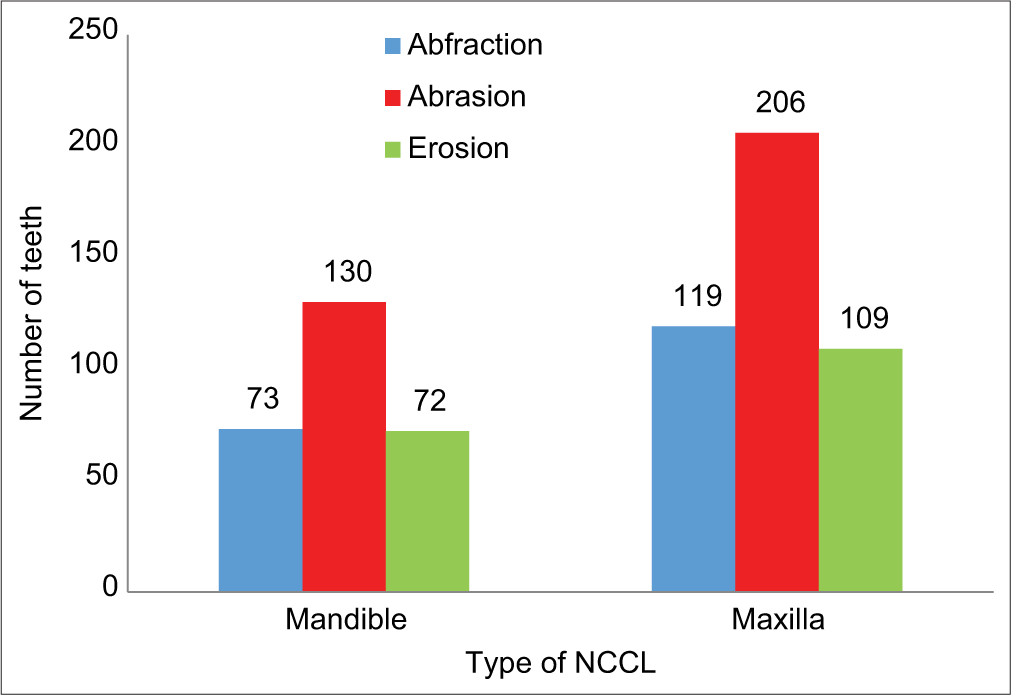

All up, there were 82 patients, with 709 teeth that were affected. Abrasion lesions [Figure 1] were encountered the most, and they concerned 336 teeth (47.4%), followed by abfraction [Figure 2], which was found on 192 teeth or 27.1%, and erosion [Figure 3], which was diagnosed on 181 teeth or 25.5%. According to the dental arches, there was a 61.2% incidence of NCCL on the maxillary teeth [Figure 4], and all the lesions were found on the vestibular side.

- Dental abrasion lesion (Kaboré, 2020).

- Dental abfraction lesion (Kaboré, 2020).

- Dental erosion lesion (Kaboré, 2020).

- Distribution of NCCLs according to the dental arches (the maxilla and the mandible). NCCLs: Non-carious cervical lesions

DISCUSSION

Restrictions, limitations, and strengths of the study

Our study was conducted during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, there were certain restrictions in place at the level of dental practices, in particular, the consultation of elderly people was strongly discouraged and limited to emergency care. It was also a single-site study. All of this could constitute a selection bias. However, the target population (survey conducted directly among patients), as well as the prospective nature of the data collection, remain the first of its kind in Burkina Faso, thereby making this work of particular interest. In addition, the clinical diagnoses were made by well-trained and experienced staff.

Prevalence of NCCL

In a review of the literature, Levitch et al. found a prevalence of NCCL ranging from 5% to 85%.[10] Our study, which reported an NCCL prevalence of 13.78%, falls within this range. This prevalence is also close to the 17.10% prevalence determined by Faye et al. in 2005 in the Dakar region of Senegal.[11] Although this study was undertaken quite some time ago, it has considerable similarity with ours in terms of the sample size (655 vs. 595) and the population studied (urban populations consulting health centers). In the study by Medeiros et al.,[17] in footballers and published in 2020 in Brazil, NCCL was diagnosed in 39.5% of the participants. Igaraschi et al.,[18] in Japan in 2017, quantified the incidence of NCCL at 38.7%. In Burkina Faso, dental surgeons have estimated that NCCLs are frequent (60%) according to the work of Ndiaye et al.[12] in 2015.

This wide variability in the prevalence of NCCL probably depends mainly on the populations studied. The low prevalence of NCCL in our series is likely to be related to the selection of subjects due to COVID-19 restrictions. Furthermore, this prevalence could be explained by the eligibility criteria of the study, which excluded a significant number of partially edentulous patients, and given that the demand for dental prostheses at the MCOH remains one of the highest in the city of Ouagadougou.

Sociodemographic factors

Men were the most affected. This has been found in several studies, although gender is not often mentioned as a risk factor for NCCL.[19-21] This can be compared with the results obtained by Kane et al.[22] in Dakar, who found a male prevalence of 46.06%. A predominance of men with NCCLs may be related to the management of urban and social demands in the setting of a poor country, which can be a source of anxiety and hence expose to the phenomenon of abfraction, which occurred frequently in this study.

This work has revealed an increasing number of patients with NCCL as a function of age, even though this increase was not linear. The average age was 46 years. With a series of 1023 individuals aged between 20 and 69 and an average age of 46.1, Que et al.,[23] like other authors, have noted this increase in NCCLs with age. Age has always been recognized as a risk factor for NCCLs. Our study found that the 40–60 years of age bracket was the most affected, at 51.2%. Paradoxically, the 60–80 years of age bracket exhibited fewer NCCLs, and this could be due to the non-representativeness of elderly people in the sample due to hesitancy in regard to consulting health services in general and certain specific services including dental surgery in particular during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Clinical data

The present study identified pain as the predominant reason (50%) for consultation. The esthetic appearance and tooth sensitivity were given as the reason by 8.5% and 13.4% of the patients with NCCLL, respectively. For Ndiaye et al.,[12] the most common reason for consultation for a non-carious lesion was pain (92%), followed by the esthetic appearance (78%) and sensitivity (74%). These results confirm the symptomatic nature (pain) of oral consultations, which also tend to be delayed in developing countries such as Burkina Faso.[24] Indeed, non-carious lesions, like carious lesions, evolve in stages or grades. They progress from tooth sensitivity to pain if no treatment is provided.

Oral hygiene was determined during this work using Greene and Vermillion’s Simplified OHIS.[14] It appears that many patients with NCCL had good oral health, that is, a much lower OHIS (between 0 and 1.2). This gives rise to the following considerations:

On the one hand, the socio-professional status and the place of residence of most patients (civil servants [36.6%] living in urban areas [92.68%]) would make them amenable to the acquisition and application of oral hygiene means;

On the other hand, focused abrasions, which were predominant in this study, appear to be intimately linked to this predominance of good oral health. Indeed, to have very nice and clean teeth, patients generally expose themselves to the phenomenon of abrasion.

Our study established the following percentages for the various types of NCCLs: Abrasion 47.4%, abfraction 27.1%, and erosion 25.5%. In the scientific literature, clinical forms of NCCLs have heterogeneous proportions. Some studies have classified abrasive lesions as being the most common, followed by abfraction and erosion, thus confirming our results. Indeed, Faye et al.[11] in 2005 determined the following frequencies for these clinical forms: Abrasion 77.7%, abfraction 12.5%, and erosion 9.8%. Ndiaye et al.[12] reported the prevalence of clinical forms of NCCL in the same order as we did, with 68%, 18%, and 14% for abrasion, abfraction, and bio-corrosion (erosion), respectively. However, Kane et al.,[22] in a study on the prevalence of non-carious dental lesions, found lower prevalences for each clinical form (25.5% for abrasion, 7.22% for abfraction, and 1.68% for bio-corrosion). However, a recent study by Ndiaye et al.[25] found an abrasion prevalence of 47%, in keeping with our findings. For the other clinical forms, our results are close to the 31% incidence of abfraction, and the prevalence of erosion of 40% remains well above what we have presented.

Other authors, on the other hand, have studied clinical forms of non-carious dental lesions in isolation, and they noted high percentages. In Nigeria, Oginni et al.[26] reported a 39% incidence of abfraction injuries. Gunepin et al.,[19] in a study of dental erosion in military personnel, published a prevalence of 38.8% in 2014. A recent cross-sectional study by Bartlett et al.[27] of 3187 patients from seven European countries found that 29% of the subjects had erosions. All of these high prevalences of clinical forms revealed by our study are explained by the lack of knowledge of the appropriate techniques for oral hygiene procedures as well as nutrition intake that lacks a dietary basis, all in association with psychologically stressed lifestyles, as the study was conducted in an urban context.[28]

CONCLUSION

NCCLs are pathologies of the collar of the tooth, which are dreaded in regard to their clinical and etiological diagnosis and for their therapy. The prevalences reported by this study are reason for all oral health professionals to bear in mind that these lesions increase over time and are a source of discomfort for patients. Prevention and early management are needed. This is why, thanks to this study, we believe that teaching dietetics, as well as appropriate oral hygiene techniques, should be promoted. Studies of etiological factors will no doubt complement the information needed for proper diagnosis and management.

Ethical approval

This study protocol has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Regional Health Directorate of the Centre (Deliberation N°2020-014/MS/RCEN/DRSC of February 26, 2020). All of the participants in the study received advice regarding measures to prevent wear and tear injuries, in addition to being referred for their care.

Authorship contributions

Concept: W.A.D.K., J.V.W.G., and K.D.; design: W.A.D.K., J.V.W.G, and D.N.; Supervision: B.F., D.N., and K.F.K.; materials: W.A.D.K. and J.V.W.G.; data: W.A.D.K. and D.K.; analysis: W.A.D.K., D.K., J.V.W.G., and D.N.; literature search: W.A.D.K. and DK; writing: W.A.D.K. and J.V.W.G.; and critical revision: B.F., D.N., and K.F.K.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lesiones dentales no cariosas en pacientes atendidos en la Clinica estomatologica siboney. Rev Cuba Invest Biomed. 2018;37:46-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple dentoalveolar traumatic injury: A case report (3 years follow up) Dent Traumatol. 2008;24:16-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Non-carious cervical lesion: Case report. Int J Med Dent Sci. 2020;9:1913-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microscopic analysis of the variations of the cemento-enamel junction in Himachali population. Int J Health Clin Res. 2019;2:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological investigation of non-carious cervical lesions and possible etiological factors. J Clin Exp Dent. 2018;10:e648-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abfractions: A new classification of hard tissue lesions of teeth. J Esthet Restor Dent. 1991;3:14-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abfraction, abrasion, biocorrosion, and the enigma of non-carious cervical lesions: A 20-year perspective. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2012;24:10-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abfraction, abrasion, attrition, and erosion In: Ronald E, ed. Goldstein's Esthetics in Dentistry. Vol 22. United States: Wiley; 2018. p. :692-719.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and etiologic factors of non-carious cervical lesions. A study in a Senegalese population. Trop Dent J. 2005;28:15-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fréquence et prise en charge des lésions cervicales non carieuses: Enquête auprès des chirurgiensdentistes Burkinabé. Rev Col Odonto Stomatol Afr Chir Maxillo Fac. 2015;22:5-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enquête auprès des chirurgiens-dentistes burkinabè. Rev Col Odonto Stomatol Afr Chir Maxillo Fac. 2015;22:5-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dental erosion. Definition, classification and links. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104:151-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk indicators of non-carious cervical lesions in male footballers. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:215-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence and morphological types of non-carious cervical lesions (NCCL) in a contemporary sample of people. Odontology. 2017;105:443-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prévalence et facteurs de risque de survenue des érosions dentaires au sein de la population militaire. Méd Armées. 2014;44:479-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tooth surface loss and associated risk factors in Northern Saudi Arabia. ISRN Dent. 2012;2012:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooth wear: Prevalence and associated factors in general practice patients: Tooth wear in Northwest PRECEDENT. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:228-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of non-carious dental lesions in the department of Dakar. Trop Dent J. 2004;108:15-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study: Non-carious cervical lesions, cervical dentine hypersensitivity and related risk factors. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:24-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recours tardif aux soins bucco-dentaires en zone semi urbaine au Burkina Faso: Connaissances et pratiques des populations sur la carie dentaire et ses complications. Rev Col Odonto Stomatol Afr Chir Maxillo fac. 2019;26:7-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fréquence et prise en charge des lésions cervicales non carieuses: Enquête auprès des chirurgiens-dentistes dakarois. Rev Col Odonto Stomatol Afr Chir Maxillo Fac. 2021;28:6-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-carious cervical lesions in a Nigerian population: Abrasion or abfraction? Int Dent J. 2003;53:275-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of tooth wear on buccal and lingual surfaces and possible risk factors in young European adults. J Dent. 2013;41:1007-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identifying the etiological factors involved in the occurrence of non-carious lesions. Curr Health Sci J. 2019;45:227-34.

- [Google Scholar]